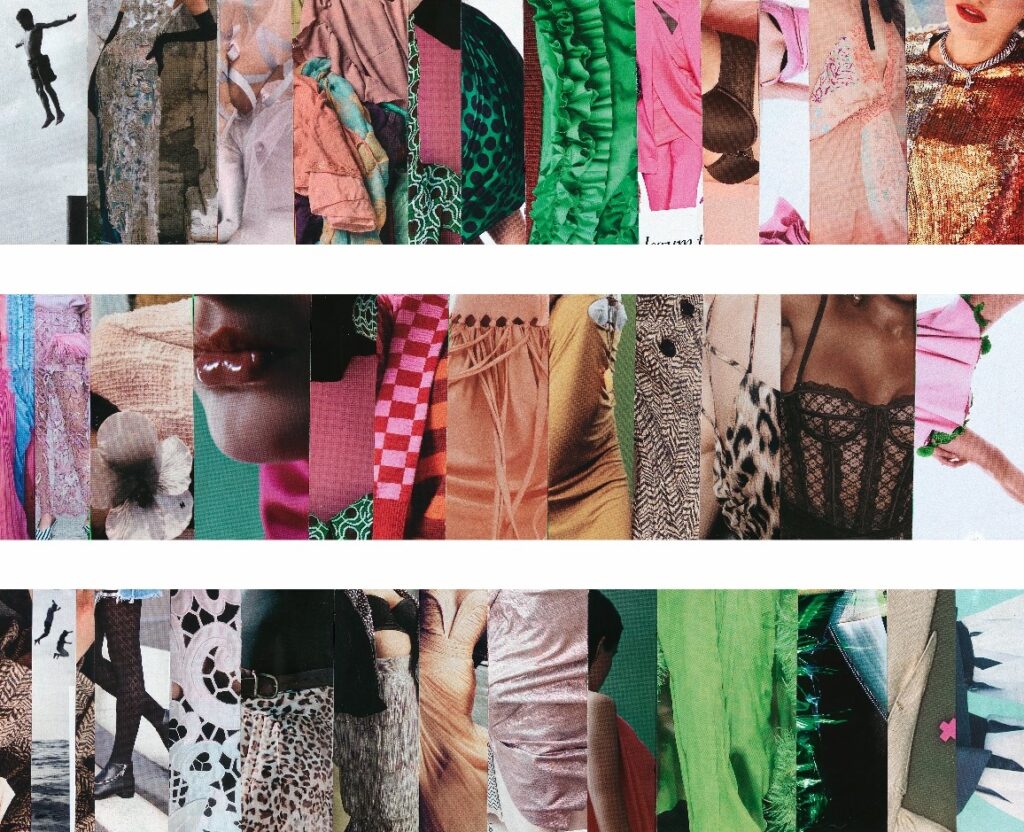

featured artist

SAVAAD FELICH | SPRING 2022

Quite simply, I’d like to discuss a number of ways to approach the collage of Savaad Felich, and I’ll be going from the very distant and tenuous to the more direct and concrete.

Firstly – and most tenuously – as Savaad has Polish heritage, these works are likely related at some level, and perhaps a deeply atavistic one, to Wy-ci-nan-ki, or Polish paper folk art, which arose among shepherds, and was initially created with shears on leather and tree bark, before the practice shifted to paper and scissors, and was brought to a high form of perfection, largely by rural women artists from the mid-1800s. And this will become relevant later.

Secondly, these collage works can also be viewed as an extension of 20th Century European collage, which began with Dada and the intentional replacement of order and tradition with chaos and upheaval; and this creative stream continued with Surrealism, in which the coupling of unrelated elements, that collage allows, was used to bring about reckonings with the unconscious.

Things however become far more biographical when we consider that Savaad’s work in collage followed on from long a career as an assemblage sculptor in metal and timber. And this was a career in which he brought disparate elements together to create new figures and abstract forms.

Events of recent years, however, precipitated a need to find a new medium for his art, and so a period of creative experimentation ensued. Artists, I believe, are fortunate in this regard. Recently, in an exhibition essay, I quoted Austria artist and architect Friedensreich Hundertwasser, who once observed that:

The profoundest form of illiteracy is an inability to create.

And there is a strong case to be made for the fact that this ability to create trumps all other forms of literacy. Perhaps because of this, there was no destabilising crisis of confidence in Savaad that I could see. There was simply an eagerness to embark upon a new branch of activity, in which abstract painting and abstract collage formed a significant part.

In relation to Savaad’s collage, what becomes profoundly intriguing to consider is exactly what effect a medium has on an artist. And to do this it is useful to consider the nature of the medium and the degree of resistance it puts forth.

Steel and timber for instance are hard and heavy, and they are also resistant to change. And so, an artist needs aggressive tools to work the matter into new forms. One thinks of the blacksmith at his forge, or of the wood sculptor among his saws and chisels. There is a specific kind of satisfaction here for the artist, that stems from a very human need to express ourselves in hardened matter.

Clay is different again. It is heavy, but not hard, and if it contains enough water, it can be worked with human hands. One thinks of the potter working clay beside his kiln. There is a very specific satisfaction for the artist here also, of a more sensual kind, that the human body can more readily relate to.

Paper is different once again, and paper rich in images of richly dyed textiles with comforting patterns and textures, and occasional swathes and patches of skin; this is at once warm, light and reassuring, and provides a quite different form of satisfaction for the artist.

At the time, I remember Savaad observing that through working in this new medium, new thought forms and new ways of imagining were induced, as though a long-neglected hemisphere of his imagination was breathing again. Or rather, it was as though a number of fondly remembered interests were surfacing.

And thus, the new medium, the new subject matter, and the new process of production lead to reflections on the degree to which dominant narratives can derail the healthy exploration of occupational and creative activites.

Interestingly enough, a friend who saw Savaads striped collage for the first time was quick to observe that the panelled strips of paper resembled bars: the bars of the cultural norms into which we are born.

And so, like all good art, these works are paradoxical. They represent ‘new possibilities’ and ‘the old cultural prison bars’ simultaneously. There are razor thin straight lines, almost invisible, and also the undulating lines of limbs and woven thread. As Friedensreich Hundertwasser once wrote:

The straight line is not a creative line, it is a duplicating line, an imitating line. In it, the human spirit is less at home.

Or rather, only by inhabiting curved lines can the human spirit feel at home.

JENNY REDDIN | SUMMER 2021

I am looking for marks that can’t be made using a paint brush or any other traditional means.

Jenny Reddin, 2012

JENNY REDDIN is an Australian painter who creates abstract works by drawing on the combined forces of chance, gravity and fluid dynamics.

These forces replace the brush in a process that breaks with tradition by privileging a suspension of rules and predetermined plans, relying instead on powers resident in acts of relinquished control.

Paint, for instance, is poured and not manually applied, and colour theory and selection play little more than an opening role, for the process relies principally on activities that occur independently and at a distance from conscious control. As Reddin has observed:

When I pour viscous solutions of solvent and pigment onto a surface, each pigment particle has a different weight, and therefore falls out of the solution at a different rate. The first to fall are the heaviest, and it is these that form the base, upon which the lighter particles will eventually come to rest, leaving tracks and traces like etching marks or the hairline cracks in oil paintings. Once poured, my only means of control is to manipulate the canvas, and thereafter simply let gravity do its work.

It is a captivating process that reminds Reddin of watching her father in his laboratory at work, where he would cook and conjure compounds in the creation of all manner of consumer products for the home. Like her father’s profession, Reddin’s practice engages elemental forces, but where chemistry prescribes both control and replication, Reddin’s discipline steadfastly relinquishes control and trusts in a process that never deigns to produce the same result twice. And yet chemistry and creativity share compatibilities and a common ancestor in the pre-scientific tradition of alchemy in which multiple layers and realities exist simultaneously, as can acts of creation, destruction, discovery and excavation, all concepts that are central to an appreciation of Reddin’s work. As Reddin herself explains:

My process is about creating beautiful surfaces that could exist somewhere in an Old World masterpiece, and then damaging them to reveal layers underneath. I am looking for marks that can’t be made using a paint brush or any other traditional means.

In the absence of a brush, pigmented planes extend in flows, rivulets divide, chasms open up, and ambiguous forms emerge charged with heightened significance. What is produced is an otherworldly encyclopaedia of forms that register in lesser known regions of the psyche, and consequently prompt far-reaching and highly individual responses.

At close range, Reddin’s works resemble intricate organic networks, and yet this inherent intricacy conceals a latent power, for as well as mimicking the tissues, fibres and capillaries of living structures, her works activate a tendency to find meaning in abstract forms, a mental activity that precedes the conscious processing of perception.

In this sense, the viewer’s engagement is in itself an act of subversion that like Reddin’s production process involves a relinquishing of control, for these works, by their very nature, prescribe a primal way of seeing, wholly unimpeded by the censoring glare of consciousness. Each of Reddin’s works act as the projection of a magic lantern conveyed with a degree of subterfuge to subcortical zones where emotions, memories, pleasures and hormones have their source.

Upon the shore of this deep spring, these privileged forms take root, attracting and absorbing a miscellany of thoughts which, although ours most fundamentally, remain mute, submerged and paradoxically unknown. It has been observed that Reddin’s works discharge an inner light. In as much as this is true, it is no doubt, as Marcus Bunyan has observed, a captured light that can illuminate both ‘the cosmos and of the subconscious’.

NERINA LASCELLES | SPRING 2019

Transcend by Nerina Lascelles positions viewers before churning seas, forbidding ravines and treacherous slopes. Elemental forces are in flux, and within this unstable environment expeditions into thick and formidably layered interiors can begin.

Inspired by the visually arresting Shanshui painting (Sansuiga in Japanese) that originated in 5th century China – paintings synonymous with mist-covered mountains and rivers fed by waterfalls – Lascelles has enacted an epic cycle of Sisyphean expanses that propel us seamlessly into corresponding landscapes of the mind.

Shanshui painting soon effected a kindred movement in poetry, in which poems were composed to be read with a specific painting in mind, while others were intended to evoke a particular image in the mind’s eye. Echoing this tradition, Lascelles has selected a Zen poem, a haiku or a poem’s title for each painting, so viewers can turn the shards of poetry over in their mind as they explore the alluring typography and the play of light and shade.

While the completion of this cycle has enabled transformations in the artist herself, from discomfort, hardship and loss to beauty, wisdom and clarity, as objects for pure meditation they have a quieting effect on the mind, dissolving notoriously fraught relationships with mundane external affairs, and in so doing opening into a psychologically purer space resembling Heidegger’s translation of the Japanese principle of iki , which he renders as ‘the pure delight of the beckoning stillness’ or as ‘the breath of the stillness of luminous delight’.

So as the many mountainous forms embody strength, timelessness and certainty, the areas of spacious light lure viewers into mystical beyonds, where form ultimately gives way to a nurturing formlessness, and where objects, emotions and thoughts are replaced by a yearning for something essential, for an essence, for a luminous presence at our core.

Like Shanshui painting and poetry, Lascelles invites viewers to embark upon journeys of contemplation encompassing birth, life, death, abundance, loss, and longing, and to pursue their innumerable corresponding journeys into poetry and art.